Since I started to “show”,1 even strangers will ask what I plan on naming my baby. It doesn’t bother me–I’m nosey myself, and in any case names are for sharing, for address–but I still tell them my husband and I are keeping it a secret. Much to my family’s chagrin, we are keeping it a secret from them, too.

I feel closer to revealing the name to these strangers; it would mean less to do so, much as it seemed less strange (and easier to feel a sort of general, easy joy) to tell my dentist I was pregnant than my friends; with acquaintances, I was a pregnant person, but with friends, *I* was pregnant. But I don’t tell our frontrunner name to the uber driver, the receptionist, or the older woman beside me in line at the post office. (It would piss off the people who care, to know that I’d told a nobody before I told them. Especially my sister ♡.)

Names are, for all their public utility and blandness, intimate. More on their blandness in a moment. Names are personal and powerful. You react to your name called before you register it. Names can be commands and pleas, are whispered in ears as turn-ons, are protectively withheld or abbreviated to their initial, are identifying, and ours.

Names are also silly. Names trend and fall out of fashion. And not just the unique names tiktok pushes at me (ohhh, I love “Timber” for a girl, the comment section coos, seemingly not hearing, as I must, the Ke$ha/Pitbull song).2 Names are silly and bland because even the most carefully selected name, with considered meaning or tradition behind it, loses definition upon investigation. There is only so much digging you can do into a name. A name is ultimately a way of pointing at a person or thing. Yes, names have strong associations for us, but these tend to be very individual, even more than associations are for words with agreed-upon meanings like “river” or “chair” or “frown.” (We are reaching the limits of what I understood of language games, full disclosure!) This the atomic quality of names: A partner will nix a potential baby name because of someone they went to school with two decades ago; one parent can think a name sounds aggressive when the other thinks the name sounds solid and dependable, and neither of them is objectively wrong.

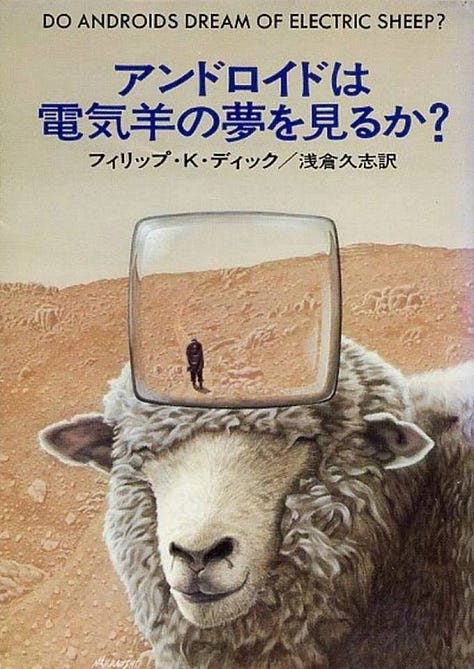

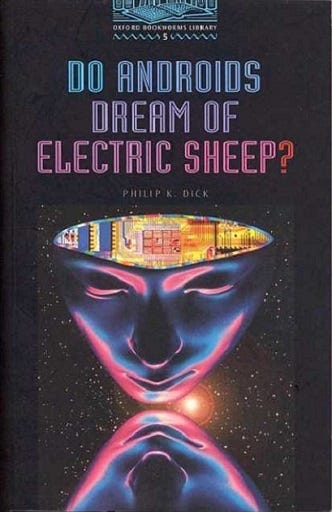

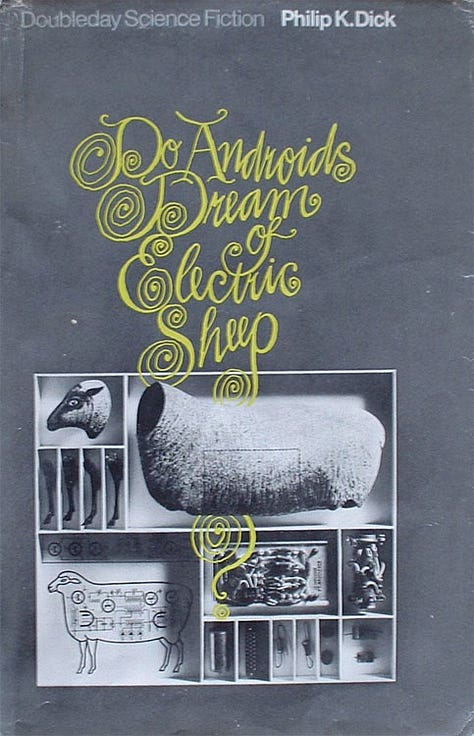

Did I mention that I changed the working title of my first novel-in-progress? It was after speaking to an editor I met at the Bread Loaf writers’ conference who said my OG title was “too genre.” Based on my description, she suggested I should target the literary reader who likes speculative elements, and not open myself up to the criticism of straight-genre readers, who can be more punitive when the book doesn’t meet their expectations.

I dislike thinking of genre (and audience) this way, but tbh I have committed to a version of this already: when I was new to the writing world I’d call my work “sci-fi” because it had futuristic, invented technologies. Seemed accurate, because I grew up reading books shelved in both general and genre—still do—and didn’t think too much about the shifts of reading tastes and marketing. But these things matter when you’re trying to sell stuff. I do write sci-fi, but I rarely call it that anymore. I use the term speculative instead, to indicate that my work is “literary” in its style and pacing, and to align with the current trends.3

I like my new title, but not as much as the old one.4

What’s in a title? Last month I read The God of the Woods by Liz Moore, a title that has little to do with the novel itself, a polyphonic literary suspense set in the Adirondacks. But it did make me want to pick up the book. Similarly: I read a fair chunk of You Dreamed of Empires by Álvaro Enrigue, translated by Natasha Wimmer, for the highbrow reasons of liking the title (and the cover).5

Currently reading Hum by Helen Phillips, a speculative dystopian novel that’s good but, well, dystopian—and since I’ve had an emotionally punishing February, I’m slow-walking my read. (In the meantime I’ve been on a nonfiction kick, including my favorites of the period: The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century by Amia Srinivasan, The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel.) Hum is a book title I like, and a technology name I like, too–it’s what the robots are called in the novel’s world.6

Lazy names are a red flag of genre dilettantism, imo. Naming is central to immersing the reader in a strange world. With speculative fiction, a genre whose “subject matter does not exist” (Joanna Russ), names must point to a referent that is not only fictional, but also imagined to represent a non-real subject. It’s an exciting writing problem, naming the unknown.

So: Why “hums?”

Why not “androids” or “robots”?

“Hum” superficially breaks the craft advice from Turkey City Lexicon, Don’t Call a Rabbit a Smeerp, defined as when “common elements of the real world are re-named for a fantastic milieu without any real alteration in their basic nature or behavior.” The rule would suggest that Phillips should simply call her robots robots, instead of coining a new word. Hum possibly escapes the Smeerp rule because it is a brand name—and more importantly, escapes the Smeerp rule for the reason anything in creative writing can escape a “rule,” as in, by being executed well.

During what I call the anxiety hours (between 3-5am)—thank-you pregnancy-induced insomnia!—I’ve been simultaneously working my way through A Clash of Kings. While George R.R. Martin may not always have original character names—first names are often simply a remixed spelling of common names (see: “Wyll”)—his place names are another matter. Winterfell, for example, is memorable, with sonic as well as symbolic pay-off. Same for props (ex: Arya’s sword, Needle).

Naming is when fiction writers should most try to think like poets. How does it sound, how does it round and roll in the mouth? Does it match or insert friction with the other names you’ve introduced into the story?

Hum and A Clash of Kings share little in common, sure. In parallel, each demonstrate what I think of as “micro-worldbuilding,” but might be as easily thought of as word choice, syntax, rhythm, and texture.

“Hum,” a name’s breakdown:

Hums are a thing (robots) and a brand—and they are sound, an action. The associations: soothing, nurturing (another technology in the book is called a “womb”), biological (the child characters have little interactive watches called “rabbits” that are painful to remove). Hums are produced in the mouth and yet often also mechanical, produced by a droning fan. Hum, therefore, straddles two interpretations of “manmade.” We learn from the story that the hums began as non-corporeal programs, language-first, and only later were encased in bodies. “Hum” emphasizes speech, or the precursor to speech, more than “robot,” which leans physical, kinetic. The hums in the novel are common as white noise, active with potential energy, and keyed to respond to human needs. “Hum” carries these connotations of both machine and maternal better than “robot” does. The technology names in the novel taken together (hum, rabbit, womb, etc) quilt into a cohesive style and thematic territory.

Names have a conjuring effect: they make things feel more real.

A performative utterance, simple as saying, “her name is ___”

Amanda ⊹₊⟡⋆

Pregnancy’s lexicon is interesting to me—don’t get me started on “quickening!”

“Show” as in visible is the obvious meaning. But “show” as performance for others feels apt too. I definitely feel pregnant, walking around with a weekly carousel of symptoms. But I felt more pregnant before, in the nervy early days, when I was less used to all the change. In the third trimester, I am pregnant to everyone around me, so yes, I am showing

This is not a made-up example, nor is it remotely the worst name I’ve encountered on the app

“Speculative” still isn’t great either, since most people don’t really know what it means!

Not sharing the this name either, sorry :)

I was trying to read it on audiobook but it wasn’t a great match for the form. May try again with a physical copy

With Hum, Phillips considers not only what to call her novel technologies, but also contains musings on the character names as well; the narrator names her children using parts from common words, as a sort of cover. Their names would blend, in a search engine’s spider crawl