When I travel in a new city, I often pretend that I live there, as many people do. I want to be a different person in a new city, to take up new habits, to wear new clothes—and I feel capable of stepping into that version of myself.

“I will tell you about it and you will read me saying the word ‘yellow’ and think to yourself science fiction.”

Ravicka, a city-state, can be visited by plane. The skies there are yellow. It has seen violence; it is newly independent. The citizens communicate via strange speech and elaborate gestures. You can journey through Ravicka in Renee Gladman’s series: Event Factory, The Ravickians, and Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge. The first is dreamlike, told from the perspective of an outsider linguist; the second is an account from a Ravickian novelist; the third is a text from Ravicka, written by the novelist’s lover. The persona1 feels consistent through the triptych, even as the perspective and styles shift, as if the medium of telling were secondary.

One way to talk about worldbuilding: Characters are a pull on their universes like a star to gravity, distorting the blanket of space. Rarely is that so true as in the landscape of Ravicka, where skyscrapers and bookstores shift to the thoughts of their inhabitants, where loneliness can blight neighborhoods, where memories pile into rubble.

There is a crisis unfolding. “In Ravicka, the missing ones are said to have gone (or been taken) further in, never outside the structure” (The Ravickians).

The world won’t make sense from one side of the bridge to the other. We can’t even escape the present tense of the title Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge.

How do we move forward?

This is Collected Fictions.

“The chief duty of the narrative sentence,” writes Ursula Le Guin in Steering the Craft, “is to lead to the next sentence—to keep the story going.” And this, I think, is different from the chief duty of the poetic line. I can pick up a book of poetry for the first time and open it to a page at any point, and while it will have been changed by the loss of context, the meaning won’t be ridiculous without it. Even within a poem, a line can call for pause, for doubling back, for questioning itself, for unfocusing your gaze. At least, if it isn’t specific to poetry, it is a common feature of poetry (and that’s the best a genre division can achieve, in my mind). A poem echoes, a story sails.

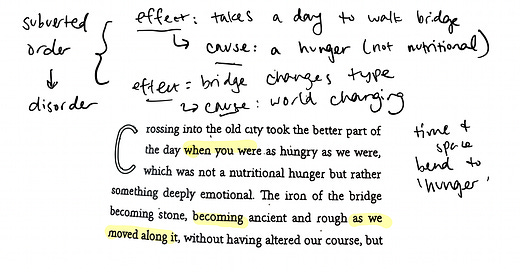

In a fictional narrative, things are. Things are and are. Fiction cannot easily bear contradictions: at a certain point, the relationship of cause and effect collapses, subverting our immersion in the fictional world. The king died, and the queen died of grief. Not: the king died, or he didn’t die, the queen survived him, dying of grief, living on. (As always, exceptions! Sofia Samatar’s “An Account from the Land of Witches” builds contradiction to fascinating effect—one that does tend to alienate many of my students, that said.) We need cause and effect even more so reading speculative fiction, so as to understand the nature of a world that might be quite different from the one we know. In The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, Gwyneth Jones writes that, “the reading of an sf story is always an active process of translation,” which is keenly felt in Gladman’s multidisciplinary, cross-genre work.

If the chain of causation is breaking down—if figurative and literal are swimming together, if the flow of time is fraught—we must look elsewhere for patterns in order to understand the world.

Where does the story return?

The Ravickians share intimacies—one woman can’t speak to our foreign traveler, so she kisses her. One subgroup of Ravickian expels puffs of air as a form of communication. Others use salsa dancing, or the cello, or spooning. Translations fail. The writers Ana Patova and Luswage Amini love each other but cannot seem to stay together, sending each other messages via courier across the city. Meanings labor over the landscape, yearning for the point of contact, for the bridge. The two lovers first met on a bridge. But the world around the bridge is changing, and the iron railings become stones. We are changing. Can we really stay in the in-between, or must we cross? These are books not only about place, but also about belonging.

I dip in and out of these pages, sinking, forgetting, trying again. The voice—the persona—is the source of cohesion, but we cannot depend on it:

I change my mind all the time. When I first began writing prose (I “started” in poetry), my essays and chapters were stilted, with silences, yes, and also with recumbent clauses qualifying and second-guessing to exhaustion. The narrative was drowning in too many versions of myself. Nothing exactly wrong with it, except when I needed movement, momentum. For time to flow. I had to say: things are, things are. I bucked it for a while; too many decisions to be made.

The mode of attention is different in different genres, which I suppose is another way of talking about immersion. What is immersion, in a poem? Several versions can coexist (what Gladman calls invisibilities or “holes” or “0“) inside a poem–that has something to do with it.

In class, Claudia Rankine once told us that a poem is an argument. I think in the sense of: a poem states a reality again and again. It twists and turns, refutes, coils, but it is always presented. There are no nothings, only voids, as in architecture: a volume contained in the relationship between spaces. The words must be kept “aloft,” Rankine said. What did she mean?

What is the energy humming beneath the web of Ravicka’s streets?—desire, I would call it, bittersweet.

I use the poetic/essayist’s terminology, instead of fiction’s ‘narrator,’ mostly out of a gut-feeling.