Have you ever been wrong about somebody or thing—your initial impression just totally off-base? Or merely felt uncomfortable because you didn’t know the lay of the land? Ask yourself: What did you rely on to make your judgments?

I recently moved to Toronto; the year before I was in Boston, the year before that I was in Brooklyn, and the year before that Providence. Lots of moving my 5 sets of 8ft-tall Billy bookcases (Ikea, pls sponsor me)…and tons of experience being new in social situations (one might expect me to be better at it by now, but alas). Point is, being new requires observing, guessing, and (sometimes) making choices based on limited information. It’s a fact of living in a complicated, ever-changing world.

You may remember from the summer my response to Parul Sehgal’s article, in which I wrote:

I do not come away from reading “The Tyranny of the Tale” with a desire for fewer stories…I come away, instead, with a desire for more varied stories. Story has so many shapes, and even within a neat superstructure of plot—the metabolic beginning, middle, and an end—there can be room for interlude, lyricism, breakdowns, formal experimentation, imperfection, indeterminacy, and mess.

And in that same newsletter, via Zeynep Tufekci and Game of Thrones, I brought in the idea of “psychological” versus “sociological” storytelling—although I don’t think they are necessarily opposed narrative strategies. Today I want to give some practical advice by talking about one of my favorite sociological stories: the film Princess Mononoke, directed by Hayao Miyazaki.1

The story begins when a monster attacks a village. Prince Ashitaka kills the monster, but in the process he is cursed and exiled, setting him on his quest to find a cure before he becomes a monster, too.

He arrives at Irontown, run by Lady Eboshi; she is at war with the giant animals of the ancient forest at their doorstep. Ashitaka also meets San (Princess Mononoke), a human raised as a wolf-girl, who is dead-set on fighting Lady Eboshi and Irontown, which deplete the forest. Thematically, it’s industrialization vs nature. Their desires are directly opposed to one another.

Ashitaka, an outsider thrust in the middle, must decide who to side with, who to believe.2 He must choose a reality among competing narratives of the world.3

***Annotated Princess Mononoke Outline (spoilers)***

I took the time to create the “reverse” outline above because Princess Mononoke manages to be complex without losing the heart of the story, to be political without getting too bogged down in detail, to include a surprising number of characters and factions…I had to lay out the structure to see the hidden machinery at work. This is a world that, putting aside for our purposes the gorgeous animation, nonetheless immediately seems thick, real. That is a rare quality. So many stories run threadbare, especially in the world-setting; the seams are visible, the weft shows through. And that is the last thing I want as a speculative reader. I want to be immersed.

How does Miyazaki do it? I could try to answer this question for a full lecture—or three—but for now let’s dive into one strategy I found while making that reverse outline, which I think could apply whenever you are trying to juggle an ensemble cast. Together we’ll look at how characters (and the groups they are representatives of) are encountered in Princess Mononoke, and how that effects the audience at each stage of the narrative:

1. Glimpse

One character observes another in action. Early in the film, Prince Ashitaka observes a girl suck the blood from a giant wolf’s wound. He does not understand.

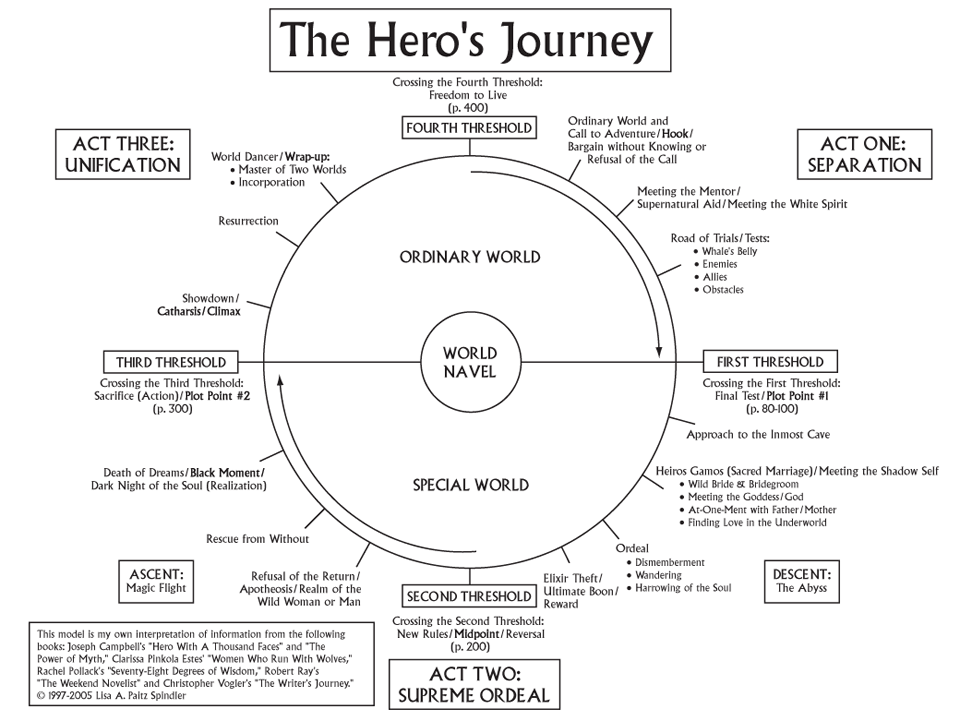

[Mapped to the hero’s journey, this is also something of a glimpse of the “underworld” or “special world” Ashitaka will later enter… a glimpse of a world, not just a character…although Princess Mononoke is not so cleanly mapped to Joseph Campbell’s meta-myth, since Irontown is strange to Ashitaka, too.4 More on this later.]

The glimpse piques the audience’s interest. It shows a single facet of San, the wolf-girl, within her place in the world—the primordial forest she inhabits. (In a short story or novel, the glimpse is a description, as in a short scene.) Thus San is “tagged” with the political/thematic group she represents, the forest gods.

A glimpse ought not to be mundane. San is shown doing something fairly important, and also strange.5 We—Ashitaka, the audience—want to know more. Worldbuilding is always at its core a bid, a curled finger saying dear reader, keep going, find out, discover.

What’s more, we see Ashitaka’s reaction (he is diplomatic, reflecting his character as peacemaker, and curious) and hers (wild, fierce). Characters are—by degrees—revealed in action/reaction.

The glimpse technique is used for various characters spanning the first act’s exposition. Note how they are seen at a distance, and even partially obscured.

2. Gossip

Characters are not separate; they exist through their relationship to other characters. Relationships make both characters seem more solid—they reify each other as they interact, want things from each other, disagree, and yes, talk about each other. Gossip is one of those basic human instincts. It can be terrible of course, but when you are new it can be useful, a lifeline.

Every character in Princess Mononoke has an opinion on each other, and as is realistic, their opinions arise from different life experiences. Their views reflect biases stemming from their social positions and histories.

In the second act, everyone is talking about San and Lady Eboshi as representatives of the primordial forest and human/tech (respectively). Sometimes the gossip seems to subvert the glimpse, sometimes it concurs. What’s great is we—Ashitaka, the audience—don’t know what’s true. We have to listen, and read in between the lines, and decide for ourselves.

Gossip is rightly suspect, incomplete. Thus the audience is active, thinking, solidifying the characters in the act of trying to get to know them.

3. Complicate

Talk becomes action. Lady Eboshi has multiple facets because we see her from different people’s eyes, and thus different perspectives. She is the ambitious industrialist, the savvy war-lord, the leader who is empathetic to marginalized people, and so on. In the second and third act, Ashitaka directly interacts in scene with both Lady Eboshi and San, finding for himself who they are. The world continues to unfold as we walk deeper into the story, gaining clarity but not losing depth.

Ashitaka is empathetic to both human and mythic worlds. He struggles to find a middle path, refusing easy answers, not pledging loyalty to either narrative, but not becoming passive. He seeks compromise, an unusual position for the protagonist. He is invested in the complexity of the story because he has seen both sides.

Returning to the hero’s journey. A better thematic patterning suggests itself, focusing not on the individual, but instead on the change in the world, tracked from the beginning of the story to the conclusion. Note that we have two initially separate worlds and understandings which Ashitaka encounters, bleeding into one another over the course of the narrative until each threatens the existence of the other. The era of gods is threatened by the era of man, but humans are not truly separate from nature; in their clash, the world is thrown into chaos; finally, a new age emerges in which neither humanity nor nature is separate or supreme.

I should say “sociological-leaning” or “using sociological tools,” as I don’t believe we need to have separate bins and throw “sociological” stories into one and “psychological” stories into the other. But that is a mouthful.

One clue that this is a sociological story is that Ashitaka (the likeliest main protagonist) is unconscious for a pretty important section in the middle of the film, and it’s chill.

One bigger clue that this is a sociological story: by the end of the movie, the world has changed more than Ashitaka (or the titular Princess Mononoke) has.

Ashitaka is not a typical male chosen one archetype, and in fact, he takes on many of the feminine masks of fairy tales/mythology. Most prominently, he is in a conciliatory role, attempting to create balance and peace. Also: He must be saved multiple times by San, he is kissed from unconsciousness like Sleeping Beauty, and he doesn’t return to the provincial home a hero, but instead begins a new life near his love.

This is not the Greek mythological glimpse of a woman bathing, although there is that reference in subtext.

I will have to watch this movie and then re-read this fascinating "box cake". As a photographer, it occurs to me that this is probably why candid/street photography is so much more engaging than posed.