Hi friends,

It’s been a little while. I’ve been in hermitage working on the final act of this novel rewrite. :) However I recently emerged from hibernation (read: my couch) to attend Ted Chiang’s talk, “Thoughts On Being a Cyborg.” (I’ve yet to devote a full newsletter to the idea-driven short story adept, but I’ve mentioned Chiang here and also here.)

A brief summary of Chiang’s lecture and discussion with Prof. Avery Slater—with the caveat that I couldn’t take notes:

Writing is not an innate skill (like speech), but rather a technology, one invented only a few times in history, and

Writing re-circuits how we think—hence we are cyborgs—to the extent that

The advent of writing represented a paradigm-shift in communication & experience.

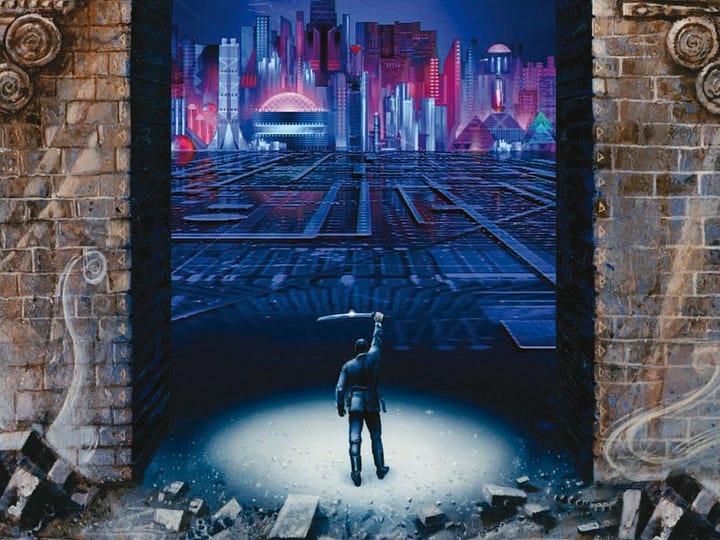

Science fiction has been great at imagining what a paradigm shift might evolve into, but ONLY AFTER the first inkling of the technology has been invented. For example, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (published 1992) extrapolates from the fledgling computer graphics of the time to imagine immersive online worlds (popularizing the Sanskrit term “avatar” in this context, as well as the portmanteau “metaverse”). Snow Crash accurately predicted the great leaps we’ve already seen—and ones we have not yet been able to produce…Tech-y people also were inspired by Snow Crash, but Chiang didn’t address that part.

Generative AI (LLMs) are NOT the beginning of a new paradigm shift. (This came up over and over in the Q&A, which Chiang rejected, along with all things Elon.) We haven’t seen the beginning of the next paradigm yet, he contends.

Something I’ve long found fascinating in Chiang’s work is his ability to escape our current dominant paradigm and cast into previous or alien modes of understanding. He does this in both the content and style of his stories, which seem to have more in common with earlier generations (Borges, Sturgeon, Ballard) than his contemporaries. Curious for an SF writer in particular, how his stories feature alchemists and philosophers as frequently as robots and the denizens of outer space.

Often we project onto the past our logics and morals, or depict humans with alien masks rather than push ourselves to imagine something different. We write historical fiction in which the white people we are supposed to root for are conveniently also on the right side of history, as if the Victorian cutpurse or feudal lord was Selected by the author-god to receive a crash course in civil rights, inclusivity, and the scientific method. Of course, it can be truly draining to read about racist/ sexist/ homophobic/ etc etc ugh-type characters, and nobody has to—we get enough of it bombarded at us, in the 4chanification of the internet and IRL. This problem is also prevalent, though, in the form of Christian ideology foisted onto pagans or capitalism/ stock-colonialism onto distant spacefarers. It’s flattening, Disneyfied and simplified, gameplay-ready-player-one-’d. It is generally applied so that we the Reader are not challenged. The arc of the moral universe may bend toward justice, but it is also long, so why does everybody seem to think the same?

“It is the magic of nationalism to turn chance into destiny.” -Benedict Anderson

And for that matter, if we suggest the characters are on the right side of history we also assume we are on the right side of history. As if the daylight between right and wrong was eternally sharp. While it’s clear we are correct in fighting for equality and freedom, it’s rare that we all agree on what that means, and how best to go about it.

I recommend this excellent essay on worldbuilding by Vajra Chandrasekera, author of The Saint of Bright Doors, which is high on my tbr—and just received a Hugo nom as well. In the essay, Chandrasekera is critical of the worldbuilding ambition:

“The world, to be built, must be made small. The technique requires the stripping away of complexities…It is common to describe worldbuilding projects as encyclopedic, but few worldbuilding projects have the space (or the interest) to investigate the depths of historical-psychological complexity, ambiguity, unknowability, and irreducibility that might be seen in the edit history of a single contested Wikipedia page—to say nothing of the epistemological failures of Wikipedia itself, its biases and overwhelmingly vast absences. Worldbuilding as a totalizing project cannot help but fail. My feeling is that “suspension of disbelief” and “secondary world” were not helpful ways to think about what is actually happening when we read a text, and yet they are tropes so influential and well-established that many of us take them as givens, as expectations of how we should read and what a fantastical text is supposedly doing.”

The givens are the issue. As writers, the question is how to see outside of the ocean we are in.

My husband (side note: you should buy his novel) takes forever sometimes to read the books I recommend. Granted, I do the same thing to him!! I retain my right to give him guff about it, though. A book I’ve been recommending probably since we started dating is Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson, which has stuck with me since I was assigned it as a bright-eyed Political Science major/Asian Studies minor. He just finished it, so after the Ted Chiang talk—while out for dinner and a flight of ciders with our friends—we immediately began relating the two thinkers.

Chiang argued that writing is a technology, and that it is substantively different from the oral tradition. Yet Chiang focused on the effect of writing-tech on the individual—transforming us into cyborgs—not so much the effect on populations. Perhaps he didn’t have time. But this was what I kept thinking about. If we are cyborgs, what sort of communities do cyborgs form?

Would you die for your country? Commit the ultimate sacrifice for someone living in, say, South Dakota who you’ve never met, or for some future American you never will? Maybe you personally would not, but many people have. In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson points out how incredible this is. The nation is not like a tribe or town. We imagine we share something important in common with Americans who live across thousands of miles or existed before our time, or will be born only after we die. A continuity that severs at the border. Then we build walls across the desert to keep people out. This is pretty weird!

Last summer I immigrated to Canada from the US. I technically live closer to my family in Los Angeles now than when I lived in New England and New York, and there is no language barrier (in Toronto, aside from some fun slang—I just learned the term “a keener”), few cultural differences aside from celsius (which I will never grasp) and the milk that comes in bags instead of cartons…but the border makes it feel further, to myself and to others.

What is especially fascinating to Anderson is that nationalism is quite recent, historically speaking, and yet commands such fervent (religious-like) loyalty. The nation-state arose under particular historical circumstances and yet is “modular, capable of being transplanted” around the world, and seems ancient, natural. Nations and their borders feel like a given, they are everywhere—and many groups of people who don’t have a nation greatly desire it. I understand well that in our current political reality, nationhood is the most probable path to security, rights, and power—that without a state, discrimination and subjugation can be difficult to fend off. The nation can offer much to marginalized peoples. But it is not the only political unit that can.

All nations were invented at a certain point in time, and like any tool, have both their uses and abuses, consequences seen and unforseen. In short, the nation is a technology, too. Why don’t we think of them this way? What is gained, if we do?

After the invention of writing came a variety of inventions to share writing: the printing press, the newspaper, the television, the internet, and finally, social media. Imagined Communities contains a wealth of convincing evidence to show that it is only after the printing press that we see the modern idea of the nation emerge

Memory accumulates with writing

The middle is getting cut out of our newspapers, our book publishers. What happens if there is only Substack (or whatever) and The New York Times left? Will the fragmentation of our media lead to the fragmentation of our sense of shared community? Has this happened already?

What paradigm might occur after the nation?

SFF right now, in movies and literature, is interested in revolution—in the overthrow of the evil empire. How many speculative works are interested in the creation or transformation of the state? I agree with Chandrasekera that “worldbuilding” in the usual sense is inadequate, in that it assumes a knowable world. What I want to add is that we worldbuild in our world all the time, and that it goes unacknowledged. So many parts of our societies are technologies we created, we imagined into being. (Don’t get distracted by whether or not a thing has cords, gears, screens!) These are technologies nonetheless that can constrain us or can work for us, that shape the way we think, that terraform our world—shouldn’t we pay more attention to them?