Monsters of clay and uranium, pt. 1

"Oppenheimer" & what it could have learned from Michael Chabon's "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay"

A two-parter, because I’ve been letting the first half of this essay sit for a long time in the drafts. (I blame moving.) Part one will focus on “Oppenheimer” and part two will address narrative solutions, with a close read of a section of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay

This is Collected Fictions.

The Prague ghetto is threatened, so a rabbi fashions a protector out of clay. Emét, truth, it reads on the golem’s broad forehead. The clay monster cannot speak, but will defend the Jews from this pogrom with incredible strength. The golem is brawn and might solidified.

Yet when the creature falls in love, it rampages. Or, it rampages without cause. Or, it rampages because of a small mistake.

The rabbi erases a letter from the broad forehead. Mét, death, it reads. The clay goes still.

I don’t often write about my Jewish identity (as I’m not religious) but it’s been on my mind since my return from a trip to Berlin and Prague. By turns purposefully and not, I visited several Holocaust memorials. I literally stumbled onto the memorial at Bebelplatz, of the Nazi book-burning of May 10, 1933, which is a sunken, empty library beneath your feet.

(Fuck the censorship of books both then and now.)

In the old Jewish Quarter of Prague they sell squat miniatures of the golem. I’d forgotten that the myth, or at least a dominant version, originated there—and that this was the European city featured in Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which I read some years ago. The novel begins as Josef Kavalier flees Nazi-occupied Prague (in parallel to the golem) for New York, staying with his cousin Sammy Clay; together the plucky pair become central makers of the Golden Age of comics. The golem figure morphs into the superhero, Americanized in splays of Ben Day dots. Eventually they are faced with the backlash of McCarthyism, persecuted by antisemitism and homophobia.

And as it turns out, while in Prague I saw Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer,” which is a very different story that spans much the same chronological and geographical space—and centering the assimilation of the Jewish diaspora. McCarthy rears his ugly head in both stories. And in both stories there are monsters, supposedly created for our protection: one is of clay, the other, uranium.

I was nineteen years old standing before the cenotaph in Hiroshima. It was a sunny day. I was there on study abroad. Through the cenotaph you can see the shell of the “A-bomb dome,” a building left in ruins. A cenotaph is a memorial to bodies buried elsewhere or else nowhere. I kept silent for more reasons than one. In my journal I wrote that it was difficult to be at the peace memorial, as an American. Problematically, I retreated into my identity as a Jew, because I was used to thinking about WWII from that aspect, and because I did not want to be aligned with the country that had done this.

Perhaps the scientists of Los Alamos believed themselves the makers of a golem, a blunt tool to herald the end of war. It is hard to imagine such fatal naivety.

I’ve come across arguments for the presence of Japanese people in “Oppenheimer,” or on how explicit the film’s political critique should be. Ultimately I think the film’s sentiment is clear, but not sufficiently real.

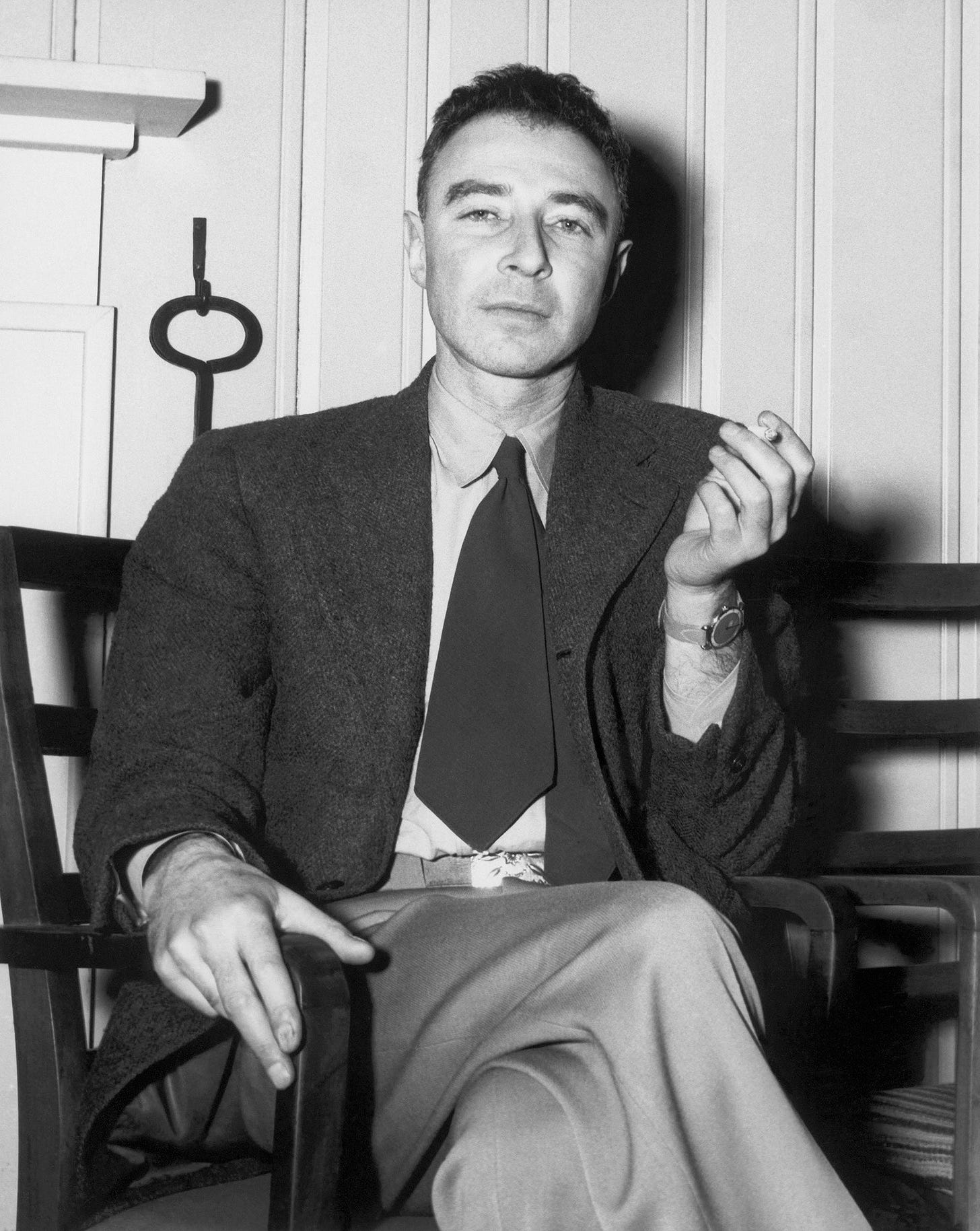

From the beginning frame to the last, Oppenheimer is the destroyer of worlds, haunted in the hollows beneath Cillian Murphy’s cheekbones. His character does not undergo change because his arc is so thoroughly preordained, as if Oppenheimer saw the future itself with those glossy blue eyes, and not just the possibilities of atomic particles.

I watched this supposed womanizer land two intelligent hotties (without showing a lick of the charm I know Murphy has in spades) and I wondered, what if on some level he made the atomic bomb to impress them.

I wondered if on some level he did it to gain access to spaces Jews were only provisionally accepted into. As a show of strength.

I wondered if on some level he did it to show up his colleagues.

I wondered if on some level he got so excited that he didn’t care if the bomb was good or not.

The movie can’t adequately make a statement one way or another, because it is so undyingly self-important. Certainly those are not the only reasons the bomb was made, but they are human reasons, and it was humans who built the bomb. The film falls for a classic trap—the protagonist has obscured the world that shaped him. We cannot see around the POV. Ironically this makes not only the world seem less real, but also the man overshadowing it.

I’m not sure how much the narrative structure of “Oppenheimer” relies on American Prometheus, the biography by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin (I haven’t read it, although I have read Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb). But I found myself wondering at the narrowness of its telling. The Rhodes book stresses the difficulty of juggling all the larger-than-life personalities involved in the technological feat of the atomic bomb, the relationships created and dashed in the process. The heist-structure Nolan is so enamored with might’ve actually worked here to show the team-building aspect (as it decidedly does not for the dramatic twist at the hearings), but instead the characters have nothing much to talk about besides either Communism or physics, even during sex. Nolan is most comfortable in explication, and so we are impressed/pressed by dialogue that talks more than it reveals.

For instance: What if the women in the film—before the final few minutes—had more room to do things besides fuck or scream hysterics? I’m all for pushing back against prudish violence in American culture, but that’s not what this is. I’m surprised Nolan doesn’t get more shit for his portrayal of women as either Moral Goodness Personified or Sexy, Doomed Creatures destined to drink/ commit suicide.

I did not feel the pain of finding out your old colleague is now a Nazi collaborator. I did not buy Oppenheimer as a playboy, as his tortured eyes never strayed far from the bomb. The scenes are so often breathless and myopic that I did not sense the humans in them. In contrast, the scene that has the most natural chronological flow, the Trinity test, is notably also the most successful at the buildup and release of tension. Incredibly, it struck me as the scene with the least spectacle, and the best in the film, because it is the most direct treatment of the material. Rarely in the film does Nolan trust the audience enough to allow us to feel.

Another scene, much lauded in other reviews, is the turning of the Los Alamos crowd after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Their cheers transform in Oppenheimer’s deep POV from congratulatory to hellish. This is what I mean by the sentiment of the film being clear: obviously this is not a pro-war scene. (I actually think the moment of Oppenheimer stepping through a charred body is too graphic, and unnecessary.) The crowd scene is good in isolation, but makes no sense in context. Oppenheimer was the destroyer of worlds from the title card. So what does this scene show? How has he changed? What personally, socially, morally has Oppenheimer lost in this moment?

He hasn’t, because the movie never truly gave those things to him. We would feel more implicated in this chapter of history if it did.