how to f*ck an alien

a 10-step guide

Or ghost, monster, faerie, android—you name it.

A primer on writing about seggs, especially when tentacles/the dead/magic/etc is involved. Jk—we can say the word “sex” here, it’s not tiktok, thank god!!

The origin for this newsletter: While traveling to visit my family in LA (we took a car trip to Joshua Tree and Palm Desert), I listened to the first eleven hours of The Book of Love by Kelly Link. It’s great! It’s also, among other things—namely grief, magic, love, friendship—about horny teenagers. The characters think about sex and relationships often, and sex is portrayed as both normal and exciting, and is at times described instead of wholly elided—a rare combo in literary fiction. Oh, and often the sex in The Book of Love is with a partner who isn’t mortal.

So, let’s have the sex talk.

Disclaimer: I have not read any Sarah J. Maas, although seemingly everyone else and their mother has. (Speaking of: Hi, Mom, I hope you enjoy this entry). xoxo

“ ‘Science Fiction’ has… a dubious if not downright sluttish reputation.” -Margaret Atwood

Questions to guide our inquiry: How much should fiction *go there*? Must it “advance the plot?” Do you agree that in our media everyone is beautiful and no one is horny? Is speculative fictional sex different, craft-wise, from regular fictional sex? And how do you avoid inducing cringe in the reader?

The following is geared toward writing literary-leaning fiction, and may not be applicable to erotica, romance genre, or AO3 (as much as Raylo fanfic repackaged with YA-ish cartoon covers has publishing by the neck these days)...no shade! Just not my field.

Okay, let’s begin, shall we?

Let the faeries have big dicks, if so desired. Sex is a part of life, fair game as subject matter; that includes all kinds of sex, although literary writers seem to prefer masturbation (portrayed pathetically, or as strange—looking at you, Philip Roth) and mediocre sex as subjects, a tendency I describe with the technical term, the “womp-womp approach,” in which sex is unsatisfying or awkward or even traumatic and rarely if ever Hot, presumably because we are a bunch of cowards. There’s a place in fiction for bad or meh sex, but it really is altogether too common.

Here more than anywhere else in fiction, we beg the reader not to take us too seriously. The other emotions we freely ask of them. Loneliness is great stuff for narration. Yearning we can do, that’s respectable. But raunchiness? Something so sincere as that? So frequently, we demure. Rather insert a white space break and let the reader’s imagination fill it in. Because good sex, explicitly depicted, flirts with the pornographic, and the pornographic gets pulpy, silly, popcorn-y. Pornographic and Artful, however, are not by necessity at odds. Garth Greenwell writes well on this. Greenwell and R.O. Kwon have also highlighted the value of queer desire as a literary subject, and how other aspects of identity (such as race) intersect with our intimate selves.

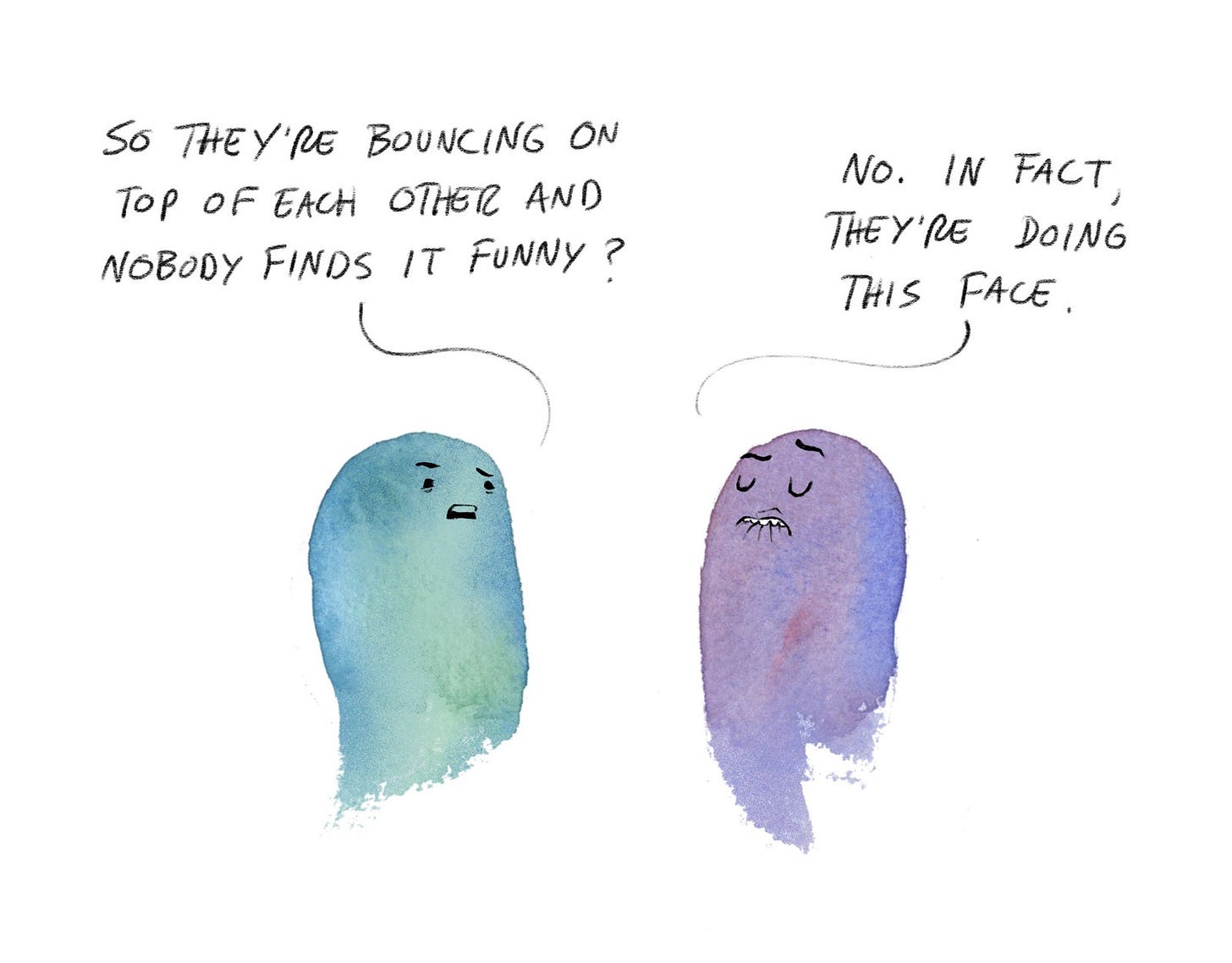

comic panel by Will McPhail, “Where Your Personalities Go While You’re Having Sex” Sex happens to characters. Garth Greenwell again: “Sex is an experience of intense vulnerability, and it is also where we are at our most performative, and so it’s at once as near to and as far from authenticity as we come. Sex throws us profoundly into ourselves, our own sensations, physical and emotional; it is also, at least when it’s interesting, the moment when we’re most carefully attuned to the experience of another.” Sex is like anything else in a novel, caught in the web of events and meanings, marriages and funerals, beginnings middles and endings, pacing and tension and release. It doesn’t have to “advance the plot” (such mechanical phrasing, ugh!) but sex always has an effect.

The “inches on the page”—pardon the pun—of description should be in proportion to importance, to mangle an Annie Dillard quote. This is my preference, over the idea that everything in a story has to advance the plot. What is gained with depiction, over summary or elision?

Carmen Maria Machado’s speculative short story “The Husband Stitch” has a lot of descriptions of pleasurable sex. This is a wonderful example, not only of how explicit prose can be artful, and that excess (check out her similes!) can be a virtue, but also how the surface of desire provides a sense of depth. Machado almost solely relies on showing the character’s lust as the means to make the narrator feel real. And it totally works. It ties into the themes (power, trust, desire) of the story, and it both belies and underlines the fairy tale -esq flatness of the characters. (The fairy tale part comes in with the source material of the green ribbon, the section headers that encourage an oral telling, and the nesting of other stories within the main story.)

Sex is both normal and transgressive. The normal part is addressed in #1. For the transgressive part: taboo is fecund territory for fiction. It’s thrilling and juicy, much like violence is. It gets at our masks and what lies beneath them. It’s a leap, a juncture, a contrast, a divide.

Euphemism is risky. I understand—there are so few good anatomical words—and it gets medical fast. But beware: I used to read slush at a poetry journal—that’s not the beware part (I recommend to all writers becoming a slush reader if you can, because you will cut more bad writing habits that way, and speedier, than any other method)—this was about a decade ago. Here is the beware part: I still remember a submission that referred to a vagina in an extended metaphor as a “scabbard.” It was…not good. But hey, I do remember it.

Avoid describing sex like it’s chess. As with all physical action in fiction, it doesn’t have to be a blocked play-by-play. I had a teacher who loved to say that “reactions beat actions,” and I think that’s generally right. Above in “The Husband Stitch” excerpt, there is physical description, but it is all grounded within the narrator’s point of view, focused on the dynamism of the scene, the shifts of energy, the buildup to pivotal moments, on how the character feels.

Ask yourself, what is sex, to your story? How are you framing it? It shifts, as all things do, with context. If you want to write flesh that has real weight, you have to flesh things out. In speculative stories, the context of the sex—what it means to the characters, the stakes and effects—might be quite different.

I find, when building out stories, it’s clarifying to start with opposites. Create foils. So: What isn’t sex, in your story? Think in terms of balance. If there is one version of something, one extreme, you should consider including its opposite as contrast (and perhaps its midpoint as well). In my newsletter “A Box Full of Eyelids,” about horror writer Mariana Enriquez, who wrote the novel Our Share of Night, which by the way is quite horny, I shared part of her interview from the excellent literary podcast Between the Covers.

The interviewer David Naimon asks Enriquez why there’s so much sex in her novel. She answers that her novel is about death, and that it is desire, not love, that is the opposite of death. This is one of those pronouncements that maybe I don’t entirely believe, but I find generative. What’s more: it is a true statement, within her novel.

You must risk cringe, for kink. In that same interview, Naimon describes how “sometimes one needs to risk pornography in the portrayal of violence.” This might be rephrased as: How much control does the writer have over the reader’s reaction to their words? What if you mean to write a sexy scene, and instead, oh no, it’s cringey?? (See #5, and this image, below)

In fiction, cringe is the experience of being “taken out” of the story. It is a problem for the suspension of disbelief. It’s easy to avoid cringe by framing the sex with sarcasm, with pity, or evading depiction (see #1). However, cringe can be avoided another way: by saturating the story in the POV. Avoid cringe with narrative distance, or else with closeness.

Sex has power dynamics. My favorite story to teach is “Bloodchild” by Octavia Butler. (Side note: we really don’t talk enough about how sex features in Butler’s oeuvre. It’s strange and interesting.) “Bloodchild” is essentially (SPOILERS) a gender-swapped pregnancy story with ambiguous consent. See the ways our understanding of this sexual experience is tied deeply to the worldbuilding, how this occurs at the level of the character, and also at the sentence, the word.

The sex is dramatized (shown in scene) which allows the sex to be complicated, and requires that the reader parse the action, the narrator’s reactions, in order to decide what kind of sex this is. Is it coerced? Are they lovers? The scientific jargon (“ovipositor,” "probing,” “puncture”) clashes with the personal (“her body into mine,” “a low cry of pain”), and the simple diction, grounded in the narrator’s feelings; “forcing” and “caged” suggest he does not consent, yet he is also jealous like a lover, has a measure of power (he moves and accidentally hurts her, and feels sorry as a result) showing that he cares for her. This contrast is the ambiguity at the heart of the story. If summarized, the sex would have to be one thing or another. Scene is for when summary is insufficient. So much is gained here by showing instead of turning away from their sex. About those tentacles. If you’ve been reading this newsletter, you know my answer at this point: You should go for it, baby. Get weird. Or just plain get different from what you think is common or expected. For instance, why should sex with an alien be the same as sex with a human? What if they were ambisexual? Game of Thrones shook up the fantasy genre in part by foregrounding a sexual morality as dark as its medieval politics. (Sometimes things that should not be radical or surprising are, given our genre history and culture. For example: Why not a classic dragon-filled high fantasy that’s also sapphic?) If your characters can live for several lifetimes in the far-off future, might they choose to experience life as various genders, and assume various roles (mother one lifetime and father the next)? If you are writing an entirely created world, why should it be hamstrung by the same prejudices as ours? Would an AI who can inhabit many bodies at once think of sex and gender as we do? Perhaps your science fantasy epic could have a throuple with a pirate. Or (below) you could imagine a very different “first contact” story…