This is Collected Fictions.

Let’s begin with Margaret Atwood, because she knows how to begin things:

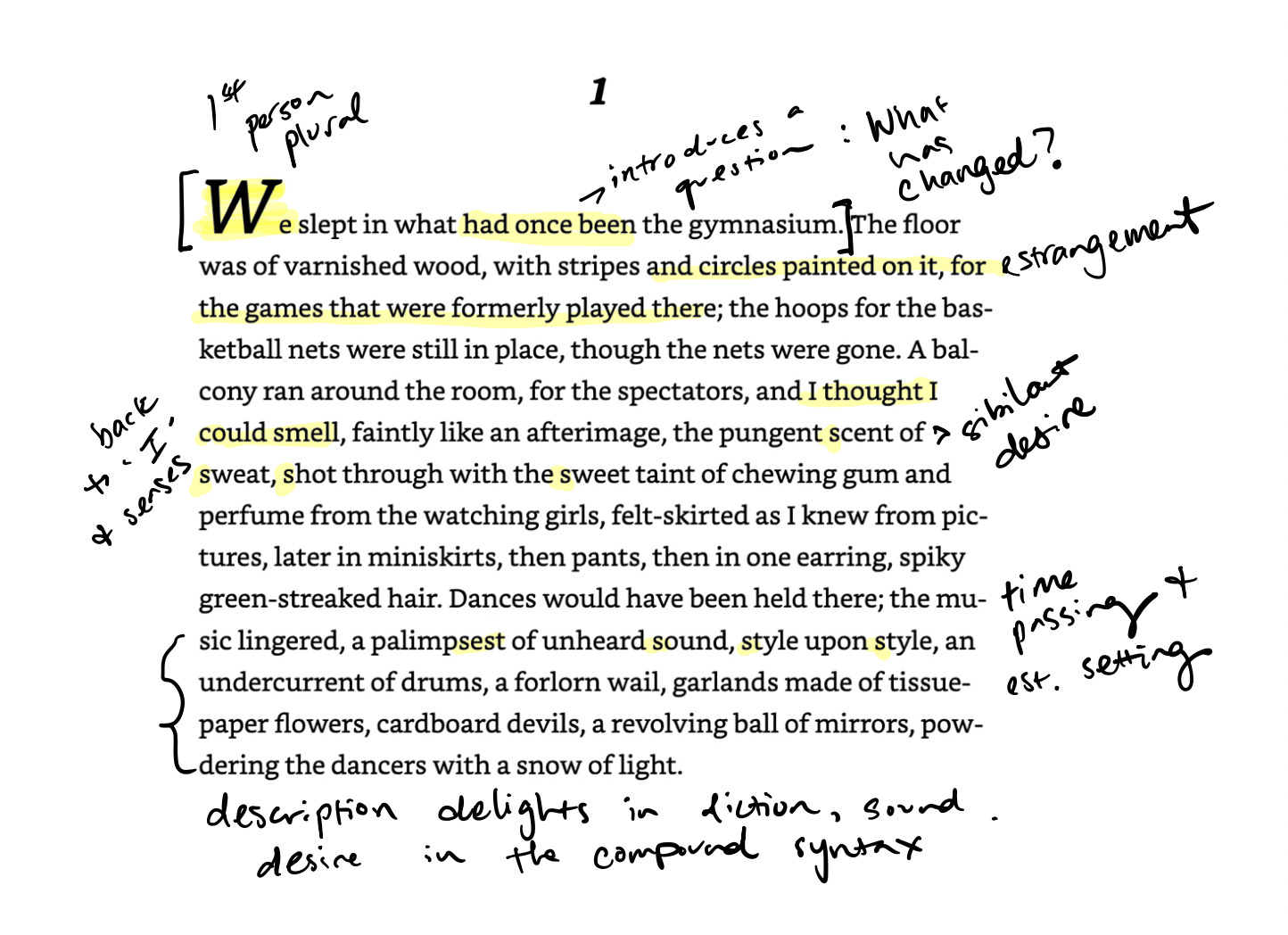

Often I hear worldbuilding discussed as if it was all lore, or magic rules, or contours on a map. But worldbuilding starts with the sentence. These first sentences are entirely atmosphere and texture, a billowing tent of world that rides entirely on a question, the basic suspense at the heart of all speculative fiction: what kind of world is it? And more specifically in this case: what has changed? Why do they sleep in what had once been a gym? And who is the collective “we?” This is what Setting is—not only a place, but a position.

(Note: The questions are not distracting the propulsion of the paragraph because they are limited, and we are grounded in the scene by the POV. “Point of view is an instrument—one of intensification; it acts, it behaves, it is temperamental.” -Eudora Welty)

Worldbuilding is staking the territory. This is a book about sex and power and freedom, and so we can find those themes here. Track those “s” sounds, the decadence of sensory detail (especially smells, the most primal of senses, but also imagined sounds) and sheer variety of things once-there and once-was, the dilation of the syntax in clause after clause—desire soaks the descriptions.

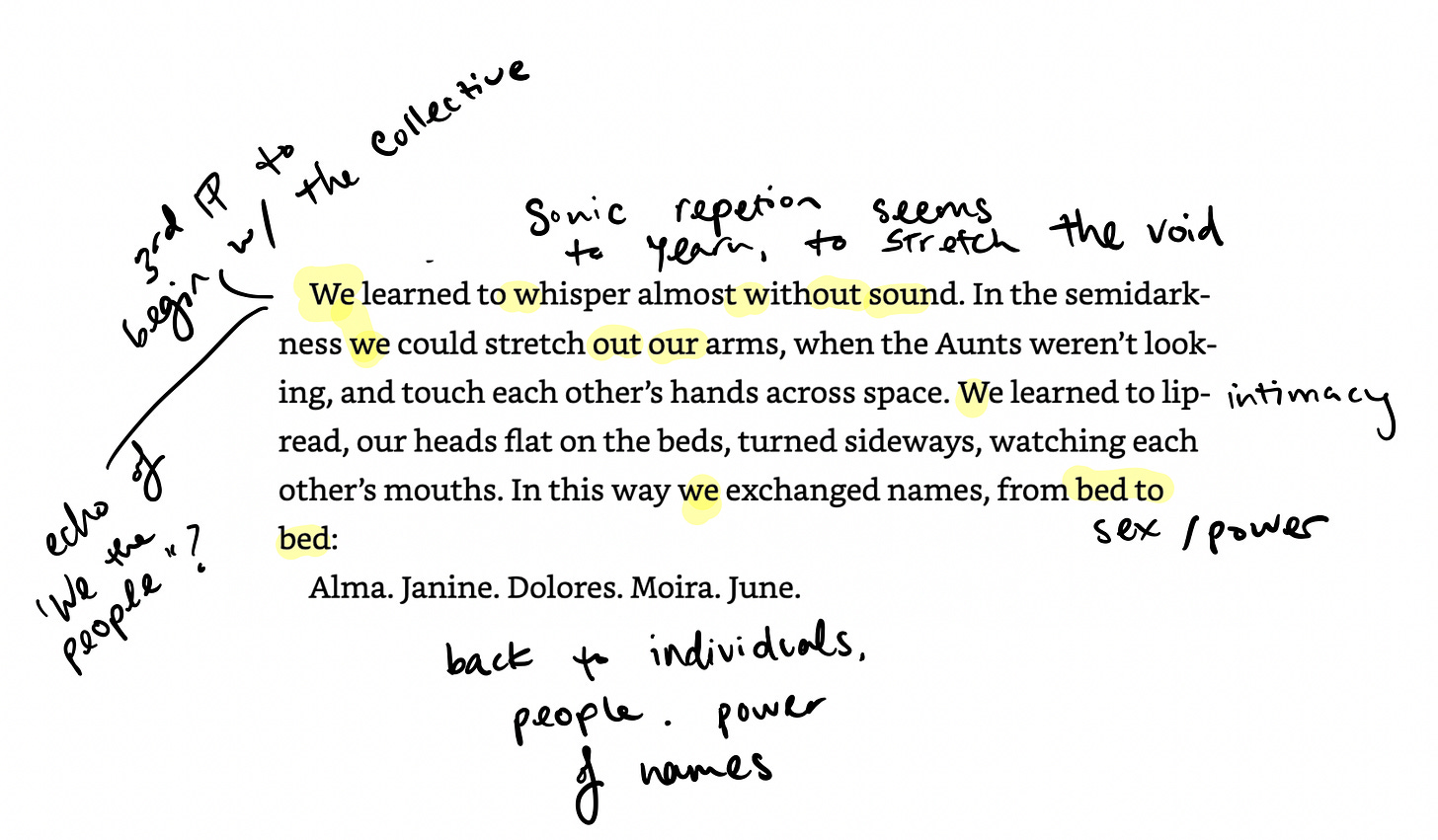

Sex, and yearning, are directly stated; the polysyllabic, latinate “and loneliness, and expectation,” then the falling back on “something…something,” enact that yearning, that reaching. Atwood is teaching the reader how to read her. She is directing us. She wants us to ask: What has been lost?

The reader is told clues about the world, but we are not explained much; we suspect the U.S. is gone, we know these people can’t leave. Violence enters the scene, tied implicitly to sex. The reader leans in to parse the clues of what happened, and what will happen if we turn the page.

Who are the Angels? They are named but remain unexplained. Orson Scott Card (bleh, but he has a good term) calls this worldbuilding tactic “abeyance.” We know enough for now: that they are related to the guards, and to those who wield guns. “Angels” suggests religion, although that isn’t explicit yet. The mystery of the story is held aloft by poles of specific, curated detail.

Rules, their enforcement, and the obstacles to escape are foregrounded. More staking of the territory of the book, and, bluntly, are a promise of plot to come.

The chapter ends on an intimate image, and images like this stick in the brain; it is the physical expression of the yearning that has wrapped itself around each word; the women (we know now from the names that they are women) reach out to each other, voiceless, but communicating across the divide. The maximalism of the previous paragraphs has focused onto only this. In just a few paragraphs the story has moved from the collective We to the power of the individual, of names. The rest of the novel is told from the first person “I.” It is a lonely place. Beginnings are for creating a language, and “I” feels different than it did before.