☆A brief entry, because I’m sprinting to the end of my novel redraft. I’m on track for my personal deadline—to finish in the next two weeks(!) before I drive down to Middlebury for the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. I’m excited to meet and learn from all of the incredible writers who will be there. I’ll report back :)

☆☆This fall I’m teaching another creative writing workshop at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies! “The Great Escape” is online, and as per usual focuses on writing science fiction and fantasy with a literary bent. More info & enroll here!

On to the newsletter proper…

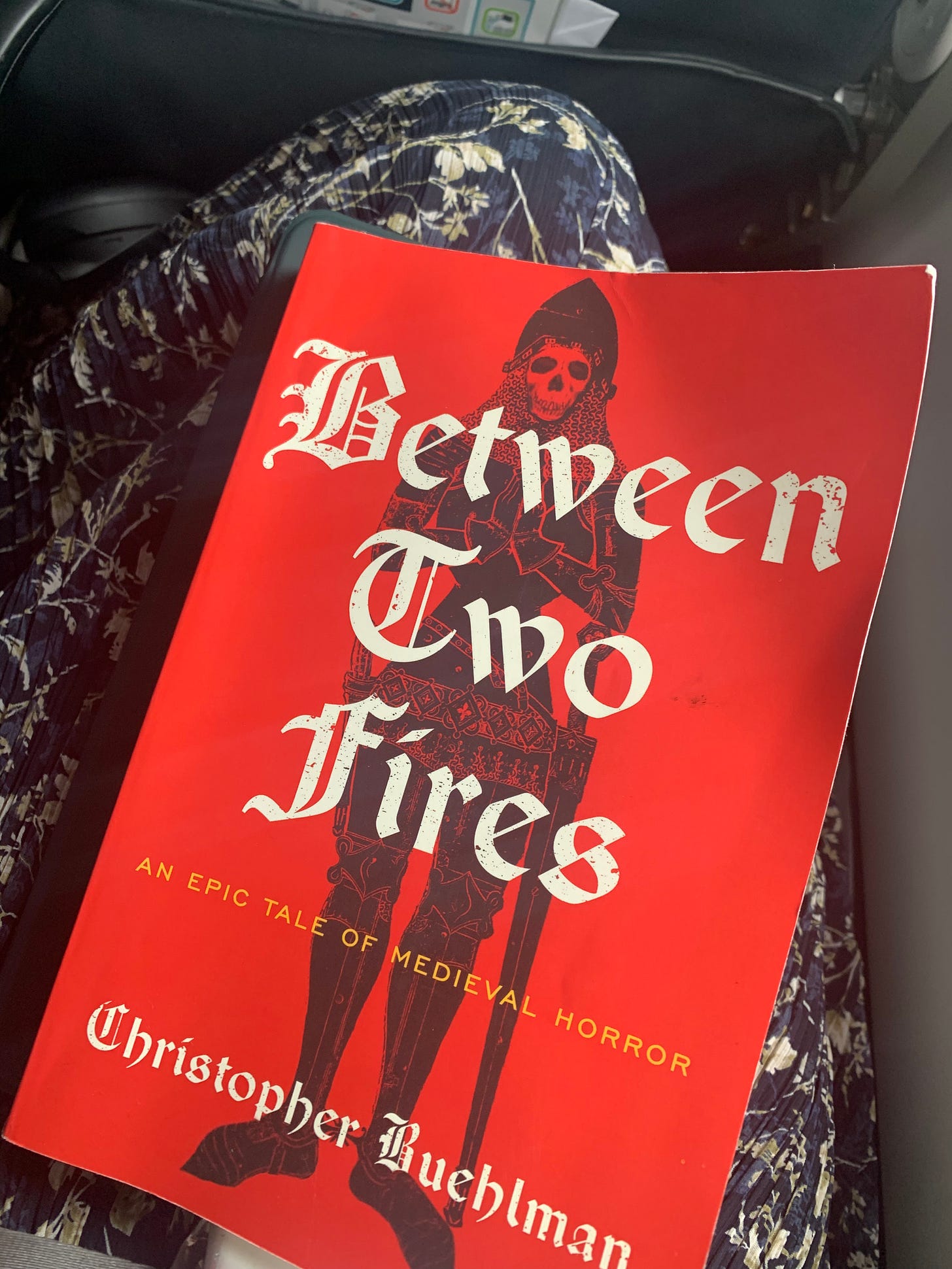

Between Two Fires, by Christopher Buehlman, is a fantasy tale about a lay priest, a fallen knight, and an orphaned girl who travel on a religious quest through plague-ravaged medieval France. It includes a lot of monster fighting, with some battles taking place on Earth, some set high in the firmament, and far, far more in the trenches of the human heart and mind. No wonder, as Temptation is a major theme of the book: in this world, the demons are real, and they smell sweet. Most of the population is dead of disease or hunger and the towns lie empty, the fields fallow. Beauty and comfort are more seductive than ever in a collapsed society. It’s the end of the world, so why not live a little?

It’s interesting that the book is categorized as Horror on the cover…I suppose I’d call it grimdark fantasy? There are horrors within to be sure; the horrors in Between Two Fires find diverse shapes, some I found hard to read (the threat of sexual assault, for instance—although I wouldn’t necessarily say it is gratuitous in the book, as it really only appears twice over 430 pages, and while it is disturbing, it is also thematically relevant). But the driver of the book is a quest, a quest seeking to return the world to a better, previous state, to return the demons to hell and the angels to heaven—which is fairly standard for fantasy. Perhaps grimdark was less common a term back in 2012?

What I found surprising was how the story forks from the trauma plot norm. Each of the characters undergoes Trauma (see the Horrors above) and their painful pasts are dramatized in lengthy backstory. Usually trauma in narrative serves to provide the characters with a bit of psychological realism.

«A Spoiler» The knight’s trauma involves his wife’s betrayal during the war. Buehlman might’ve included the betrayal simply to give the protagonist some depth: his past hurt is the source of his gruff personality, etc, etc. However, the narrative moves through this mode and into another.

The backstory is not separate from the present plot, it is an obstacle preventing the knight’s self-actualization and success in his quest.

If you’ve been reading this substack a while, you’ll know I sometimes find trauma plots irksome, not only because they are dominant but also because they can erase ambiguity. They can be narrative dead-ends. Explain-away-ers. Ah, we say, the character thinks himself impossible to love because he has been betrayed in the past. As if reading is about cracking a code, not experiencing a story. This doesn’t have to be so, but too often it is. What’s more, trauma as a framework has a tendency to—although again, does not by necessity!!—focus on the individual self instead of on how people exist together. Looking ceaselessly backward and inward. Still, I would not call this book an “anti-trauma plot” narrative. Rather, Between Two Fires favors a frankly Christian iteration of the trauma plot, which requires the radical forgiveness of another: if the knight cannot forgive his wife, he cannot defeat the demon.

The disgraced knight must see beyond himself, beyond his own perspective, and look outward with sympathy, or he will fail.

☆